UM Student Heals Self and Community

MISSOULA – On Saturday, May 13, Christie Farmer will walk across the University of Montana graduation stage.

It is the end of one path and the beginning of another in her winding journey through drug addiction, motherhood, prison, treatment, faith, community and recovery.

At seven years sober and 44 years old, Farmer stands firmly planted and confident, despite a life of telling herself that education would never be an option.

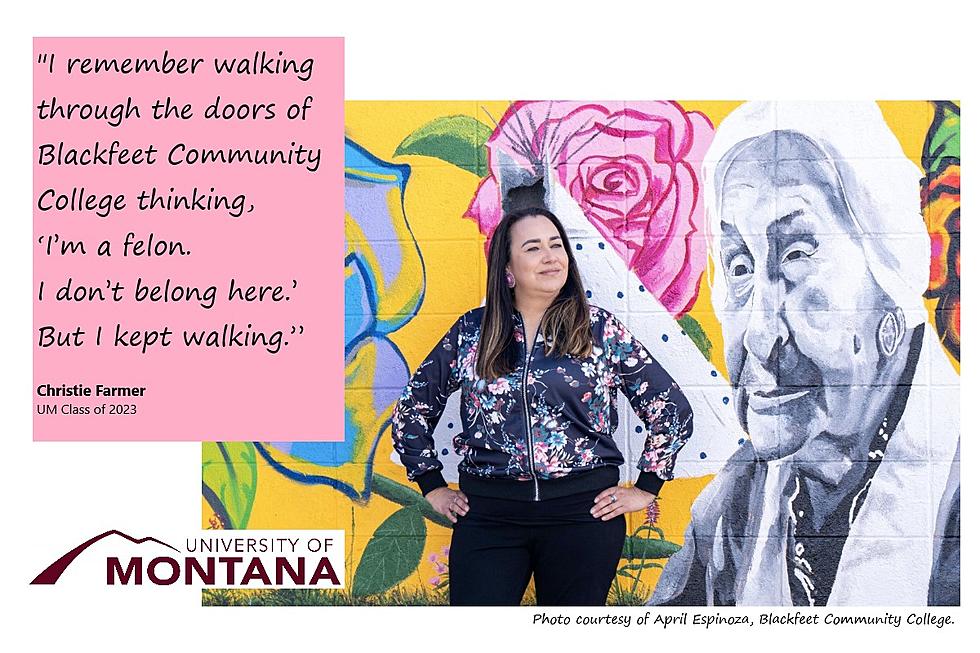

“I wanted something better for myself,” Farmer said. “And I remember walking through the doors of Blackfeet Community College thinking, ‘I’m a felon, I don’t belong here.’ But I kept walking. Never in a million years did I think I would get to where I am now.”

From Browning, Farmer is a student in UM’s School of Social Work, housed in the College of Health. For the last two years as a student at BCC, she’s completed UM classes through the University’s 2+2 Bachelor of Social Work program.

The 2+2 program caters to students who have completed or are enrolled in an associate’s degree program at partnering colleges across Montana. Students can take classes remotely through UM and ultimately earn a bachelor’s degree – without having to leave their home community.

In her time as a UM remote student, Farmer has conducted research, studied and honed a skillset around critical issues facing both the nation and her own reservation.

Among them: opioid awareness, addiction counseling and a critical need for recovery programs and policies that support a vulnerable and rural population.

“There’s a level of education that this community needs, especially in those positions where you’re dealing with huge public health issues and problems,” Farmer said. “The more education we have, the more we can begin to address the issues at a systems level.”

At BCC, Farmer’s passion for addiction education began with an internship with the Rocky Mountain Tribal Leaders Council, which led to a grant internship on drug prevention and opioid awareness in the Browning community.

The project, “Blackfeet Opioid Prevention Project through Public Health Workforce Expansion in Indian Country,” was aimed at community education on opioid addiction. And for Farmer, the best way to communicate the dangers of addiction was through public art. The canvas in this case was Browning’s Glenn Heavy Runner Pool, where many local kids hung out on hot summer days. Farmer worked with local artist Jesse Des Rosier to paint a mural on the pool’s main wall.

“In our culture and our community, there are threads of family that begin with mothers and grandmothers,” Farmer said. “So, we wanted to show the harm addiction does to families in a painting and show community wellness in art.”

Farmer was among a group that published the results of their work in the Journal of Indigenous Research. Later, Farmer and colleagues organized a drive-in movie showing of “Inside Out” with popcorn and shared information and resources on overdoses with the crowd before and after the movie.

Her work continued after being asked to participate in drafting the Montana Substance Use Disorder Task Force Strategic Plan with the Department of Health and Human Services, and in 2020 Farmer received Montana’s Student Volunteer Award from former Montana Gov. Steve Bullock.

In between, Farmer made time to complete two associate degrees at BCC and UM while holding down a full-time job at the college and balancing motherhood, a partner and grant work. She even made the President’s List for a 4.0 GPA.

But Farmer said, “It’s not so much the classwork that’s hard, it’s the weight of the larger problem, which is lives ruined by the drug crisis in our community and in our state.”

For Farmer, navigating through drug addiction is real. Having served time in prison for selling, she knows what it takes to recover. She said “being on the other side of it” allows her a deeper appreciation and understanding of what people truly need to get clean and make a life.

“I didn’t have anyone I could relate to when I was getting sober,” she said. “I remember being in a really dark place and wishing the person at the other end could really understand. I want to be that person now. The person that can relate and see it all from a bigger picture.”

. In Montana, the opioid overdose death rate for Indigenous people was twice that of white people from 2019 to 2021, according to the Department of Public Health and Human Services. In most of the state’s reservation communities, treatment centers are available, but the wait for one can be long and the centers are often far away and struggle with staffing. Farmer said her bachelor’s degree in social work will allow her a springboard to deepen her work in addiction treatment and education.

“I want to get a wider bird’s-eye view of drug addiction and recovery in Montana, not just here in Browning,” she said. “I want to look at this from a statewide public health angle. There are barriers to success when it comes to all of the agencies and courts and the actual population that’s being served.”

Graduates from the 2+2 program go on to serve as addiction counselors, integrated health care workers, court advocates, child and family services personnel, community organizers, policy workers and more.

When it comes to what’s next, Farmer said she’s not sure, but it’s clear there is more work to accomplish.

“God isn’t done with me yet,” Farmer said. “I’ve got more work to do. Work that contributes to my community and makes a difference in people’s lives. That’s the work I’m called to.”

- by Jenny Lavey, UM News Service -

More From K96 FM