MSU Research: Alfalfa Weevil Resistant to Common Insecticides in Montana

BOZEMAN — Forage alfalfa, the third most valuable exported field crop in the United States, may be at risk from the alfalfa weevil, a pest that has established itself across the western U.S., due to the insect’s resistance to common insecticides, according to a study published by a Montana State University student.

Erika Rodbell, a doctoral student in the Department of Plant Sciences and Plant Pathology in MSU’s College of Agriculture, studies invasive insects that impact field crops. Her paper, “Alfalfa Weevil (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) Resistance to Lambda-cyhalothrin in the Western United States,” written with her MSU academic adviser Kevin Wanner and researchers from the University of California, Davis, was published in the Journal of Economic Entomology last fall.

Producers across the West, including Montana, have reported significant issues managing the insect with the standard insecticides on the market, Rodbell said.

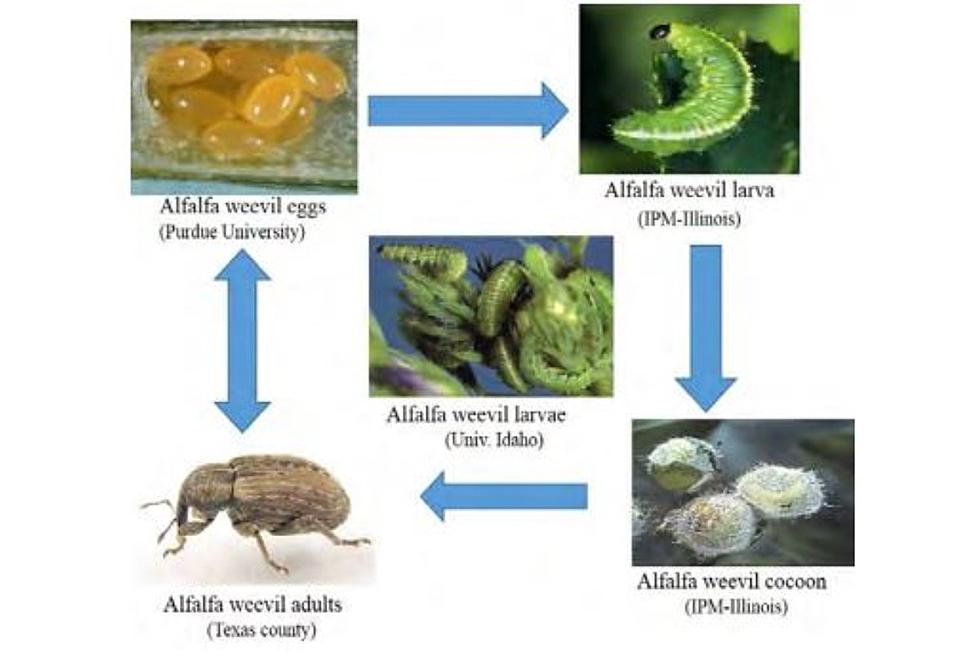

“The alfalfa weevil is a defoliating insect, which means it’s destroying the leafy green goodness of the alfalfa,” she said, explaining that the larvae chew the leaves and cause the most economic damage to the plant. “It was becoming a significant pest.”

Insecticide resistance begins to develop when significant numbers of the pest survive after the standard amount of an insecticide is properly applied.

“Producers were losing most of their (crop) yield because it was becoming an outbreak level that they couldn't manage using pyrethroids,” Rodbell explained.

The researchers investigated insecticide resistance in alfalfa weevils in Arizona, California, Montana, Oregon, Washington and Wyoming. They discovered that the weevils were resistant to both lambda-cyhalothrin and zeta-cypermethrin, also known as “Warrier” and “Mustang Maxx,” respectively — two insecticides approved by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency for managing alfalfa weevils, .

The research confirmed the insect was showing resistance to one of the most common insecticide ingredients called type II pyrethroid. The study also showed that the older, less potent type I pyrethroid — commonly called bifenthrin — was still working on the insect, Rodbell said.

Wanner, co-author on the paper and MSU associate professor in plant science, said that the insect’s resistance was not uniform. There were still areas in each state studied where resistance had not developed to the type II pyrethroid.

“It gives us the opportunity to make recommendations for how to slow the development of resistance in these areas to prolong the usefulness of this insecticide,” he said.

The paper includes suggestions for preventing and combating resistance. In Montana, alfalfa weevils tend to be most active in early and mid-June, Rodbell said. Proper monitoring of weevil populations includes recording alfalfa damage before and after insecticide is applied to track potential resistance issues.

“The best method for delaying or combating resistance is a strong integrated pest management system, which relies on robust monitoring,” Rodbell said.

Current management recommendations include harvesting early when possible, applying insecticide treatments at the highest labeled rate and rotating insecticide types. Rodbell said switching insecticides is more effective than continuing to use one that is becoming less effective. She also noted that combining different management methods is usually the best approach to preventing insecticide resistance.

Once resistance occurs, effective management options are limited, she added.

“Surprisingly, we know relatively little about this pest species even though it's been around since 1904,” said Rodbell, who plans to continue her research into the weevil’s reaction to pyrethroids to help improve current management strategies. “Producers are losing alfalfa quality and value. It’s an important issue for Montana and researchers.”

- by Emme Demmendaal, MSU News Service -

More From K96 FM